|

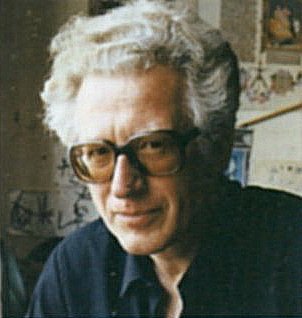

Helmut Birkhan

Born

in Vienna in 1938, Helmut Birkhan took his degree in old-age

Germanistics; since 1972 he teaches ancient German language

and literature at the University of Vienna. Since 1997 he

also is emeritus professor of Celtology. His broad interests

also include Neerlandistics and Arthurian legends. He applies

a comparative method to all these subjects, therefore he

is working on a very wide cultural front, in contrast with

today's tendency to overspecialize in quite narrow, self-contained

small boxes. He is the Author of several books, generally

on topics connected with Germanistics or Celtology.

|

|

| |

|

The

interpretation of the saga according to Helmut Birkhan

Birkhan

begins by stating that the story of Moltina,

the marmot-bride, closely resembles two great themes of the European

legends, that of the "swan's children" and Melusina's

one. The former saga, that appears in the German literature since

the late XII century, narrates of a man who captures (many versions

tell how in different ways) a swan-woman. She is subjected to

many bitter humiliations, but generates him seven children, who

have the capability of turning into swans. One of them loses the

ability to turn back into a man, but leads them all by means of

his prophetic virtues. On this subject, Birkhan remarks that,

both in the German-Celtic cultural environment and in India, the

figures of women-waterbirds usually take definitely erotic features

and occupy a place of some importance in mythology.

Melusina, on the other hand, is a woman-looking fairy, who develops

a fish/serpent/dragon-like tail every saturday. The ancestor of

the house of Lusignan marries her, accepting her prohibition to

look at her in her bathroom on saturdays. The fairy generates

him several children but, when he violates her taboo and discovers

his wife in her semi-animal aspect, she disappears forever, although

she always keeps her supernatural blessing over her descendants

and her husband's house.

The analogy between Moltina's

and Melusina's tradition cannot be considered as a valid parallel

anyway, because in ancient Europe neither snake-goddesses nor

marmot-goddesses are known (with the exception, maybe, of Echidna,

the half-animal woman, ancestor of the Scythians).

It

is worthwhile, on the contrary, to examine the concept of totemism,

against the now obsolete opinion by Lévi-Strauss, who deemed

it little more than "an erudite prejudice". Today totemism,

i.e., the belief that certain animals, plants, objects or abstract

elements, are one's own "relatives", which it is forbidden

to "consume", is considered as "a moral institution

which humanity possessed over thousands of years". It can

be demonstrated that totemism has been widely diffused in Europe

also. One of the most conclusive evidences of this fact is the

high number of tribes whose name can be traced back to animals,

like the Celts Brannovices “Raven fighters ”,

Epidii (People of the horses), Cornavii/Cornovii

(The horned ones), or the middle-Irish Osraige (Co. Ossory)

< *Ukso-rigiom “Kingdom of Deers”, or

respectively the German Ylfingar, Hundingar,

Myrgingas “People of the mares”, Cherusci

“People of the Deer”, Lemovii “The

barking ones”. Indeed, this can be traced back to a heroic

warlike attitude, or to the ecstatic state of a warrior, animal-like

in a metaphorical sense. Totemism can more safely be accepted

when the animals-relatives have no heroic features, like the Britons

Bibroci “people of the beavers”, or middle-Irish

Bibraige, “kingdom, people of the beavers”,

who are clearly corresponding to the hispanic and bithinian Bebrukes.

This way we can also explain, maybe, the Celtic tendency to derive

people and person names from botanical entities: gallic Eburones,

“people of the yew”, Betulius “son

of a birch-tree", etc. We only find a few instances, anyway,

of people names derived from "swan". Moltina's

saga appears therefore to be connected with totemistic concepts

(Moltina's daughters

are "marmots" as well), although her husband behaves

exemplarly, in comparison with later franco-german instances,

and is therefore rewarded with the kingdom. The later breach of

the totem will bring to the Fanes' destruction.

Birkhan

agrees with Ulrike

Kindl in stating that Dolasilla's

warlike character has presumably been exaggerated by Wolff for

the sake of German heroic sagas, and that both Dolasilla

and Lujanta are

marmot-persons. However, Birkhan sharply disagrees from Kindl

when the latter considers Dolasilla

as a huntress instead of a warrior, and therefore turns her into

a lunar goddess. He also heavily criticizes Kindl's

attitude to interpret most of the legend "on the guidelines

of an astral mythology".

The

paper

shortly examines, at this point, the meaning of the "low-mythology"

figures, anguane

and salvani,

with reference to Kindl's

opinion, who sees them as a personification of the local primigenious

powers, water and wood, and to M.Alinei's one, who interprets

them as a wife-husband couple in a structural opposition. But

Birkhan introduces the hypothesis that in these characters the

remembrance of ancestral forms of social aggregation may survive,

"the mythical and ritual roots of which are dispersed in

legends of this type". In popular traditions, myths survive

better than rites, as there are many myths on which no rite has

ever been founded, while practically all rites are backed by a

myth, i.e. they represent the repetition of a primigenious action.

However, it is often impossible to determine whether a popular

legend was derived from a myth or from a rite. The trace of a

rite, in the Dolomites, can better be found in Spina-de-Mul,

who clearly is the result of a masquerade for ritual purposes.

“That legends founded on a myth can convey historical remembrances

over a span of several centuries in the frame of an ancient oral

culture, is seldom historically demonstrated, but surely at least

occasionally". Birkhan quotes some examples of legends based

on historical tales and demonstrated by archaeological findings,

and guesses whether the salvans can be the remembrance

of a historical population, as it happened to the Nordic giants

and to the Finns, seen as a people of wizards.

Birkhan therefore tries to propose, as a counterpart to Kindl's

"meditations", a historical interpretation of the Fanes'

saga. He also takes into account a "political" interpretation

of both totems, marmot and eagle, supposing that the "eagles'

party" were a pro-Roman party. He however rejects this idea,

because the oldest tradition spoke of vultures, not of eagles.

The Ladinian word variöl

has the proper meaning of "piebald animal". The “one-armed

men” can be considered as a demonization. Therefore, we

may be dealing with a "clan of the vultures". Birkhan

sharply criticizes Kindl

when she proposes that the Fanes' legend came from the East with

the barbarian migrations. There is no reason why the myth cannot

be autochtonous, and we cannot understand why an imported myth

should have been so carefully preserved, if we suppose that an

ancestral myth might not! The modest and anti-heroic character

of the marmot directly speaks in favour of the antiquity of the

myth. He concludes: "I see no reason to doubt about the transmission

of the totem along a matriarchal lineage, because in totemism

this is just normal and is thence an evidence of the antiquity

and authenticity of the totemistic tradition", which should

be traced back to "the deep of prehistory of ancient Europe".

The survival of such ancestral concepts "in the myth, and

then in the legend, is the primary source that feeds the currents

of tradition".

|