The

Fanes' saga - Researches on the legend

A

short history of the studies on the legend

|

The

Ladinians

They

are the original inhabitants of the Dolomites. Pinched between

Italians and Germans, they number today about thirty-five thousand

people. They speak a neo-latin language, likewise named Ladinian,

that is subdivided into as many dialects as there are valleys,

but closely resembles Friulian and Grisons’ Romansch.

The three languages must once have been a single one, widespread

all over central and eastern Alps.

The

Ladinians’ DNA is very different from that of their neighbours’,

but they are highly differentiated among themselves also, therefore

representing a riddle for geneticists. They are known to descend

from a population, named Rhaetians by the Romans, that endured

several Celtic and Latin infiltrations even before the early

Middle Ages, when it was wedged and divided by Franks, Bavarians,

Slavs and so on.

Although

deeply attached to their language and their traditions, the

Ladinians have long been at risk of losing both, squeezed as

they were between two mighty cultures like the Italian and the

German ones, on the verge of even giving up the pride of their

national identity. Only at the end of the nineteenth century,

in the age of nationalisms, a few people started recovering

and revamping the ancient traditions, of which the legends represented

an essential part.

Orally

handed down one generation to the next, in an environment where

writing was almost inexistent, at most limited to official acts

compiled in a foreign language, legends had long been preserved

almost intact. Although regarded with hostility by the Counter-reformed

church, they really declined only when literacy began to replace

the oral tradition as a cultural standard; at the end of the

nineteenth century the tradition-preserving community had almost

vanished and just a few old men remembered scattered, generally

short fragments of what once had been a rich and compact corpus.

We must remind, among the first who gave impulse to the wearisome

revitalization of the ancient legends, don Giuseppe Brunel and

Tita Cassan from the Fassa valley and Wilhelm Moroder-Lusenberg

from the Gardena valley. We shall examine now the most significant

authors in some more detail.

|

Hugo

de Rossi

Ugo

or Hugo de Rossi or Hugo von Rossi [de Santa Juliana] (1875-1940)

was born in the Fassa valley, lost one arm in the first World War

and lived at Innsbruck since then to his death. In 1912 he collected

his “Tales and Legends of the Fassa valley – 1st

Part”, published today, in both German-Ladinian and

Italian-Ladinian versions, by the Istitut Cultural Ladin "majon

di fashegn" of Vigo di Fassa (1984, edited by Ulrike

Kindl). Unfortunately, the second part never followed, as

it should according to the Author’s intentions. It was expected

to contain a lot of fresh material relevant to the so-called “Trilogy

of Fassa”, compiled by Wolff.

A

honest and careful scholar of folklore, although he didn’t

consider himself as an expert, de Rossi transcribed everything

that people reported him, not allowing himself to introduce variations

and taking diligent notice of the variants he possibly discovered.

His collection is of the utmost importance for, among others,

the traditions connected with the pre-roman Fassa, with the Roman

conquest, with the anguane and the salvani (i.e. wildmen); Wolff

himself, who was in touch with him, derived several themes from

him. Unfortunately for our purposes, the passages directly dealing

with the Kingdom of Fanes are very few and of little relevance.

|

|

Karl

Felix Wolff

He

was born in 1879 at Karlstadt, today Karlovac in Croatia, son

of an Austrian officer and Lucilla von Busetti, a woman from

the val di Non. His family moved to Bolzano when he still was

a little boy. There, Wolff listened to his first Ladinian legends,

narrated by an aged nanny from the val di Fassa. Later on he

got in touch with some Ladinians who strived to get their language

and their traditions back into use: Cassan, de

Rossi, Moroder-Lusenberg. He became a journalist and a writer,

but never stopped wandering all over the Dolomites, his pocketbook

at hand, questioning common people, specially the most aged,

in the hope that they could convey him a new legend or a new

detail. At first his interest was mostly focused on the closer

and more familiar Fassa valley, but later on he extended the

range of his researches to all other Dolomitic valleys, pushing

as far as Cadore and Alpago. He died at Bolzano in 1966.

He

published the results of his research stepwise, until he had

composed a trilogy: I monti pallidi (The Pale Mountains); L'anima

delle Dolomiti (The Soul of the Dolomites); Rododendri bianchi

delle Dolomiti (White alpine roses from the Dolomites). His

books appeared in several editions, at times with different

titles, over a wide time span. They are available today in the

edition by Cappelli (Bologna), in their Italian translation,

and by Athesia (Bolzano), in the German original. Wolff additionally

published a wide number of articles on several different magazines,

as well as many booklets and leaflets. People interested in

his complete bibliography can find it in Ulrike

Kindl (1983): Kritische Lektüre der Dolomitensagen

von Karl Felix Wolff, Band I: Einzelsagen, Istitut

Cultural Ladin "Micurá de Rü", San

Martin de Tor.

The

importance of Wolff’s work for the rescue and revitalization

of the ancient Ladinian legends can hardly be overestimated.

There are good chances that, had it not been for him, today

we would know close to nothing about the Fanes. Unfortunately,

however, Wolff’ methods were not as rigorous as they should,

and he didn’t care recording what he had collected exactly

the way it had been narrated to him. His position was that of

a writer and a poet (and maybe, as a highly cultured man, a

good Austrian and a germanophile, he also felt a little superior

as well); therefore in good faith he made his best to restore

and refurbish, and allowed himself to twist the story a little

bit, sometimes even to insert a few missing pieces, in order

to obtain (inconsciously?) that the result might look a little

closer to the general picture he had in his mind. His

hand is usually visible, and therefore the “restored”

parts can easily be removed, but we are often left in doubt

whether something not completely understood or not completely

original may remain unaccounted for.

|

|

| |

| |

Karl

Staudacher

Son

of an hotel owner of Brunico, Karl Staudacher (1875-1944) when

still a small boy listened to the tales of the Fanes’ kingdom,

recounted by girls from the val Badia who had a job at his father’s.

Having demonstrated a great talent for studying, he became a priest

and worked in several parishes; never, unfortunately, in areas

that might allow him to collect additional material on the Fanes.

In 1921 he got in touch with Karl Felix Wolff,

to whom he made available several fundamental elements that were

known in the val Badia but not in Fassa, and lie at the very root

of the legend (marmots, vultures, twinnings…). Alas, he

was no anthropology student, and even no folklore lover: the Fanes

interested him primarily as Nibelungians’ epigones. In effect,

he left us a boresome epic poem, written in perfect German verses,

Das Fanneslied (1928: available by Tyrolia, Innsbruck-Wien 1994).

In his poem, Staudacher almost punctually conforms to the plot

of the story as reconstructed by Wolff, although

he sometimes deviates into shocking directions, often according

to ethymological interpretations which look both daring and naïve.

(As an instance, he derives Duranni from Thyrrenoi,

accordingly identifying them with the Etruscans and locating Ey-de-Net’s

home close to Florence; at the same time he identifies the Caiutes

with the Celts – whose kingdom’s capital town was

Brescia!).

|

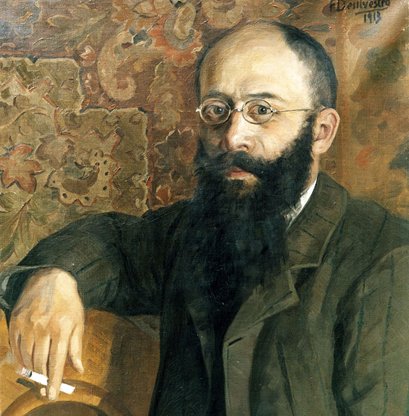

K.

Staudacher as painted by J.B.Oberkofler

(from Das

Fanneslied, Tyrolia ed.)

|

Angel

Morlang

Angel

Morlang (1918-2005) was born at Pieve di Marebbe and spent his

whole life in the Ladinian valleys. Like Staudacher,

he took orders as a priest. He had several interests; for instance,

he also was a good painter. In 1951 he published, in the Ladinian

dialect from Marebbe, “Fanes da Zacan”

(Fanes of Old), reprinted by the Istitut Ladin "Micurá

de Rü" of San Martin de Tor in 1978.

His

text was written as a script for an open-air popular drama,

what Wolff (who greeted it enthusiastically)

had long been longing for. As a matter of fact, it was repeatedly

performed at La Valle and San Vigilio di Marebbe. Morlang substantially

follows Wolff’s version, however

with a few noteworthy exceptions (e.g. Spina-de-Müsc

instead of Spina-de-Mul, the vulture taking back his

place usurped by the eagle…). A few differences can merely

be connected with staging requirements, while others may hint

at an effectively different tradition from the val Badia (e.g.

the single campaign from the Pralongià to the

Furcia dai Fers), and others are probably just a good

Christian’s misreadings, like Dolasilla buried

by Ey-de-Net. The mountain priest’s moralistic lectures

are regrettably well visible and abundantly strewn.

|

|

Modern

Critics

Wolff

apart (who perceived their importance, but never got a full

and clear picture), as far as I know, the first to understand

the anthropological implications of the Fanes’ saga was

Kläre French-Wieser, who in 1974 published

an article, “The Fanes’ Kingdom – A Matriarchate

Tragedy” on the Bolzano magazine “Der Schlern”.

The

most significant scholar in modern studies about de

Rossi, Wolff and their collections

is anyway Ulrike Kindl. She teaches German

language and literature at the University of Venice and masters

all three languages, Ladinian, German and Italian. She edited

both de Rossi’s collection of tales

and legends (1984) and the symposium held in 1985 at Vigo di

Fassa on the same subject. She certainly is the top leading

authority about Dolomitic legends. She is the author of several

books, among which both Kritische Lektüre der Dolomitensagen

von Karl Felix Wolff, Band I: Einzelsagen (1983) and Kritische

Lektüre der Dolomitensagen von Karl Felix Wolff, Band II:

Sagenzyklen (1997), where she thoroughly analyzes Wolff’s

complete literary production and expounds it with great depth

of thought.

Professor

Giuliano Palmieri,

from Treviso (1940-2007), is the author of several archaeological

researches. He wrote together with Marco, his son, I regni

perduti dei Monti Pallidi (“The lost Kingdoms of

the Pale Mountains”) (1996), where he ingeniously probed

into several aspects of the Ladinian legends, specifically investigating

several details of the Fanes’ Kingdom. He later

on published Le antiche voci dei Monti Pallidi (“The

ancient voices from the Pale Mountains”), mostly devoted

to different topics, of great cultural and anthropological interest,

but where one can also find several themes strictly connected

with the legends collected by Wolff.

In

the year 2000, Helmut Birkhan, an Austrian

professor from the University of Wien, published an essay at

the meeting "AD GREDINE FORESTUM 999-1999". After

comparing the Fanes' saga with other ancient European legends,

he tries a "historical" approach to the interpretation

of the legend, without pushing into much detail, and concludes

by accepting the authenticity and antiquity of the "anthropological"

core of the saga.

One

year later, Veronica Irsara, from San Cassiano,

took her degree discussing a thesis about the Fanes. She establishes

an original compromise between prof. Kindl's "subjective

method" and prof. Palmieri's "objective" one.

|

|